Don’t give advice, ask questions.

Most people who have meritocratically risen the ranks to managerial positions have done so because of the skills and knowledge they’ve acquired to become valuable to their companies. They know more than their newer employees and do have good advice to give.

However, telling people the right answer isn’t always the quickest way to get people to the right answer, nor to get them to come up with the right answers most often. Telling people how to do things can also dampen creativity, reduce independence, and stunt longer-term development.

Ironically, the more you instruct and rescue, the more dependent your people become, and the more work you end up having to take over.

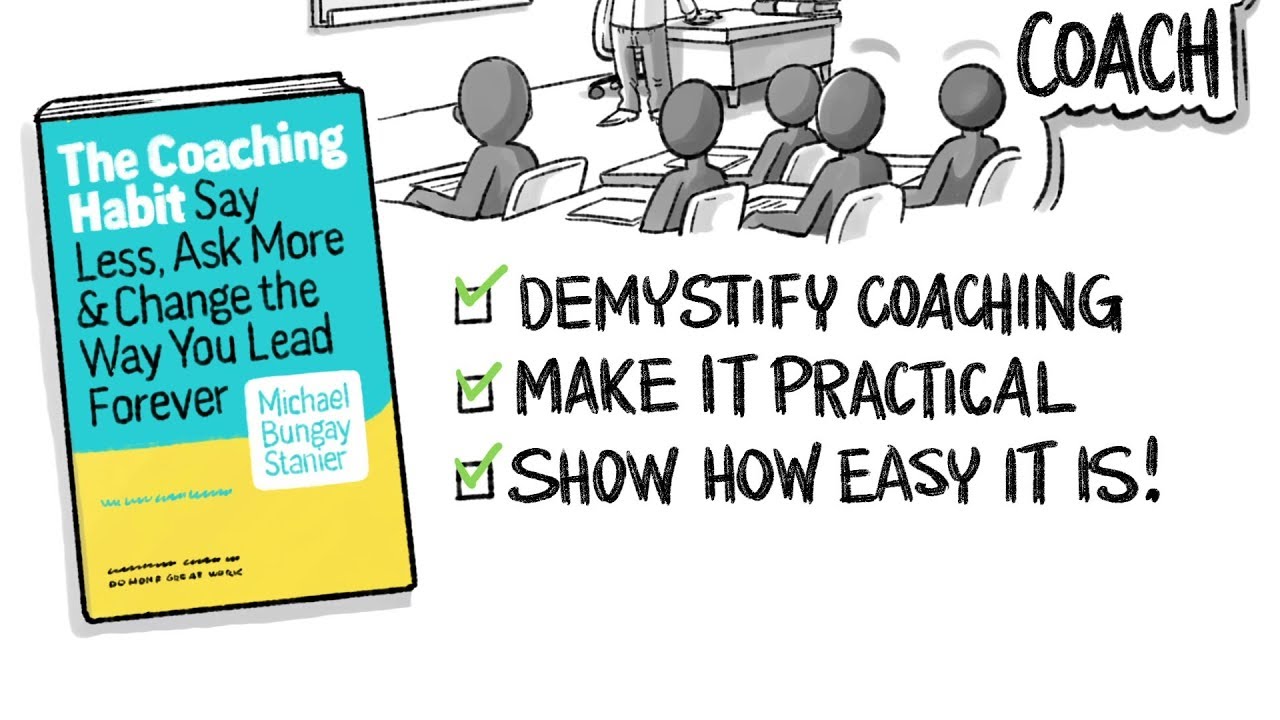

Instead, The Coaching Habit by Michael Bungay Stanier says you should ask questions that encourage people to come up with answers themselves and become problem solvers, resisting the urge to become an “advice monster”.

The book contains 7 key questions to make for better conversations that encourage development, a closer work bond, and encourage people to find answers for themselves. I have not included Question 6 in this Coaching Habit book summary review as it is less relevant to quick tips, and more something to absorb through reading the entire book.

How to act when coaching

The author also has eight quick tips for how to act when asking questions to get the best results. I’ve included seven:

- Ask one question at a time: once you’ve asked a question, be quiet and wait for the answer

- Get to the point and ask the question: if you know what to ask, get straight to the point and ask it. If it’s a difficult question, you can lessen the tension by adding “out of curiosity” or something similar before the question.

- Don’t give advice disguised as a question: saying “have you thought of…?”, or “did you consider…?”, and then giving advice does not count as asking a question. If you have an idea, wait and ask “and what else?”, and the person will often come up with the very idea you’re thinking of, and if they don’t you can then offer your idea as an idea, not as a disguised question.

- Ask questions that start with “what”: Questions that start with “Why” put people on the defensive. They can sound judgemental or accusatory, and also asks for more detail on the problem as if you’re trying to solve it yourself, leading to overdependence. Instead of “why did you do that?”, you can ask “what were you hoping for here?”.

- Be comfortable in silence: If you ask a question and they’re silent for a few seconds, they’re likely thinking deeply and creating new neural pathways searching for the answer. This is a good thing, and you don’t need to interject, even if it is uncomfortable.

- Listen to the answer: Always be curious about what the answers you are getting are. Be genuinely interested and present, don’t let your mind wander. Encourage with nodding, any noises or ‘mhhhhm’s’, and maintain eye contact.

- Acknowledge answers: when someone gives you answers, say things like “yes, that’s good,” or “I like that”, instead of rushing to give advice or asking “and what else?”.

- The Kickstart Question

“What’s on your mind?”

A reliable way of turning a chat into a real conversation. It’s not too open, nor too confining, and quickly invites people to get to the heart of the matter and share what’s important to them at the time, while also remaining focused so they only share the most important parts.

It says “let’s talk about the thing that matters most”.

Usually, the thing is one of the 3 Ps: Projects, People, or Patterns. Projects involve what is being worked on, People involves the people involved in these projects, and Patterns involves behaviour partners and ways of working that can be improved.

Once you know which one it is, you can delve deeper into this in a more targeted fashion.

- The A.W.E Question

“And what else?”

With such little effort, this question creates more of everything: more insights, more possibilities, more wisdom and more self-awareness. It unearths new ideas and ways of doing things.

The more options you have, the less likely you are to make the wrong decision. When you use “and what else?”, you create more options — and often better quality options — that lead to better decisions.

You can ask it more than once as your responses get further in. Until you hear “there is nothing else”, you can keep inquiring — but then wrap it up. When there’s nothing else to be unearthed, load the question with wording like “is there anything else?”, inviting closure but still allowing anything important to still be said.

If you’ve already asked someone “what’s on your mind?”, and gotten a response, you can then ask “and what else?”. Or if someone tells you about something they intend to do, you can challenge them with “and what else could do you?”. Or if someone’s bringing a new idea forward, and you want to explore their courage and creativity, you can deepen this thinking by asking “what else might be possible?”.

The Focus Question“What’s the real challenge here for you?”

This gets to the point — and action — quicker, so you spend more time solving the real challenge, not just the first problem brought up.

The “for you” part personalises the question to the person, forcing them to prioritise what the biggest problem is. It also shifts the conversation to bring forth more personal insight and makes for a more development-oriented conversation, encouraging growth.

If someone brings many problems to you, force them to pick by asking “if you had to pick one of these to focus on, which one would be the real challenge for you?”.

Using the first three questions

When starting with “what’s on your mind?”, you entice open yet focused answers. Then check in with “is there anything else on your mind?”, so they can share any additional issues.

For more focusing, you can then move on to “so what’s the real challenge here for you?”. Then, you can add “and what else is the real challenge here for you?”, if you want to prod further.

- The Foundation Question

“What do you want?”

Often, we don’t know what we want. A major cause of miscommunication is assuming we know what each other wants.

Wants are also surface-level things, merely the tactical outcomes we aim to get from a situation. This could be finishing a project by a certain date or knowing whether your attendance is mandatory for an upcoming meeting.

TERA describes four primary drivers behind our behaviour:

- T for the tribe: whether you feel like someone is on your side, or opposition.

- E for expectation: if you know what’s coming up then you feel safer.

- R for rank: whether you’re more or less important than someone. If your status feels diminished, the situation feels less safe.

- A for autonomy: whether you believe you have a choice in decisions.

Asking “what do you want?”, increases the T part as you’re asking what they think, putting them on the same side as you. It improves autonomy as they feel involved in the decision-making process, and therefore increases rank as they’re helping make decisions.

- The Lazy Question

“How can I help?”

Instead of assisting someone, often, when you offer to help, you’re subconsciously one-upping yourself, lowering their status and making yourself relatively more impressive and important.

It’s unintentionally condescending: having the ability to help someone involves you having skills, competencies or efficiencies (to have the time) that they don’t have.

The Karpman Drama Triangle says we bounce between three archetypal roles:

- Victim: you believe your life is so hard and so unfair, and it’s never your fault, but theirs. This has benefits: you never gain any responsibility to have to fix problems, and Rescuers are drawn to help you. But you never have power or influence and are known to be ineffective.

- Persecutor: you think you’re surrounded by idiots who are worse than you at everything, and everything is their fault. Though you have a sense of power and control and feel superior, you then end up responsible for everything, and your bullying creates Victims. You micromanage, and people only do the minimum for you. You don’t trust your peers and feel isolated.

- Rescuer: You interpret everything as your fault and responsibility, continuously jumping in to try and fix things. You believe you’re indispensable — the fixer — and feel morally superior, but people reject your help, and you create Victims because you’ll clean up after them, perpetuating the Drama Triangle.

We play all three of these roles, sometimes within the same exchange with someone. But most people are Rescuers most of the time. But you only exhaust yourself and irritate others.

By asking “How can I help?”, you force your colleague to make a direct and clear request, and stop yourself from thinking about how you could best help them.

In some niche situations, you can be even more direct and ask “What do you want from me?”. This reduces the conversation down to the exact thing they need from the chat, and you can soften this by adding “out of curiosity”, or “to help me understand better”, beforehand.

- The Learning Question

“What was most useful for you?”

Rather than learning when you tell or show someone how to do something, people learn most effectively when they reflect and recall how they did something, and what happened.

By asking “what was most useful for you?”, you induce double-loop learning. Whereas the first loop is trying to fix the problem, the second is learning about the problem at hand, creating new neural pathways and gaining insight.

When we take the time and effort to generate knowledge and find an answer rather than just reading it, we remember much more. This is why asking questions that generate the answer are so much better than just giving the advice. Tell someone something, and it probably doesn’t go in, but have them create the answer, and it probably will.

You can also ask “what have you learned since we last met?”, or at the end of a conversation, ask “what did you want to remember?”, or “what did you learn?”. It encourages people to find the big thing worth remembering, makes it personal for them, and gives you feedback on what they think is important.

Putting the first and last questions together

Using the first and last questions as a sort of “coaching bookend”, you can start with “what’s on your mind?”, and then finish with “what was most useful for you about this conversation?”. The first question focuses the conversation on what matters, and the last question extracts what was useful and shares the wisdom while making the learning more sticky. You can also say what you found useful about the conversation, building a stronger relationship.

Daniel Kahneman discusses the “Peak-end rule” and how we evaluate experiences and how they are heavily influenced by the peak of the experience, and by the ending moments. This question creates a positive finish that makes everything before that feel better.

Get new content delivered directly to your inbox.